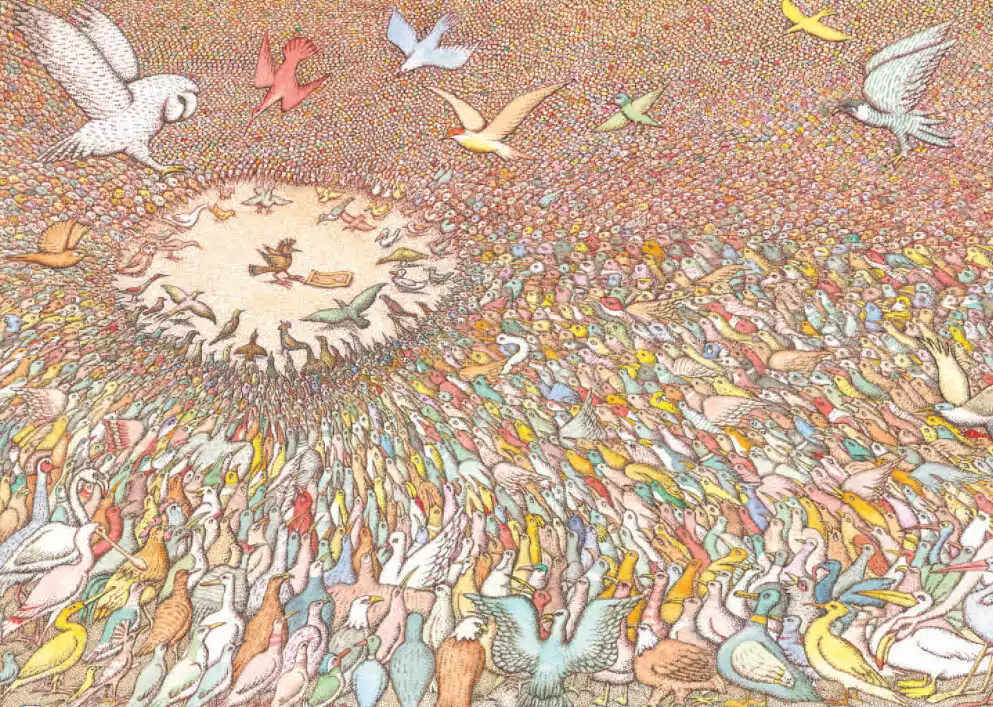

Farid-ad-Din Muhammad Attar, one of the pillars of Persian poetry, wrote some masterpieces which exerted conventional poetry beyond the limits of worldly desires and carnal affections. Farid was the only one among the Sufi poets’ cohort who dedicated all his work to Sufism. One of the masterpieces is the “conference of the birds”, originally written in Persian. It is centred around Sufism and signifies the quest of a soul to unify with God. The book is mainly considered a guidebook for the novices setting off on the journey of Sufism. Conference of birds narrates the story of birds from all over the world gathered to find a sovereign for them. Hoopoe being the wise of all, lead the journey of the birds towards their destination. Farid-ad-din gave this prestigious role to the hoopoe in the light of the story narrated by the Holy Quran about King Solomon and the faithful companion hoopoe. Hoopoe told the birds that Simurgh was the only righteous king of the flock, but reaching to Simurgh was going to be daunting. It further said that the birds ought to cover seven valleys to reach the Simurgh. The first one was the valley of the quest, the next being the valley of love, where love surpasses reason. Then there was the valley of knowledge, detachment, unity, last but not least, the valley of bewilderment, and finally, the valley of annihilation. Anyone who sets aboard the journey must need to cross all the valleys to find eternity and unification. After the hoopoe’s speech, the other birds put their concerns, lackings, and hesitations to accompany the hoopoe on the journey; through allegory, Fard-ad-Din attar addressed the human concerns and answered them by narrating the parables and anecdotes.

The fourth valley, as per narrated by the poet, was the “valley of detachment,” the aspirant moves beyond the worldly illusion of one’s self. Farid-ad-Din, in the original context, portrayed the valley of detachment as a frozen tempest. Once the seeker reaches up to the state, he has to unlearn all the knowledge acquired in the previous valley of wisdom as the valley unveils that the worldly things we put so much attention to are small insignificant things. The realization is because the aspirants compare his human desires with all the reality that encompasses divinity. According to Farid, detachment is a livid flash of the flame having the potential to bring hundreds of words down to ashes.

The fundamental characteristics of the traveller attained in this valley are gratefulness and submission. The submission and acceptance process is the essential key in Sufism, in which the aspirants put aside their self and transition to reconnect with the inner self. The theory of detachment is governed by losing the person. The lesson about human nature and virtues is unlearned in this valley, as stated above. Thus the stage can be regarded as the detachment from worldly feelings. Life is marked by unavoidable changes; by hook or by crook, we have to adapt to them either willingly or unwillingly. Life becomes lethal when a heartbreak caused by worldly desires makes life worse than death; this is the point where mourn and remorse find a way in humans. However, the valley of detachment makes the happiness and grief sourced by worldly desires equal in potential, and the seeker becomes independent from the mundane input. The aspirants (Sufis), no matter how poor and deprived they look socially but internally, have been bestowed with the profounding gift of spirituality. In reality, it is the subjection to suffering that brings the ultimate wealth of contentment and eternity.

After addressing the concerns of the birds and counselling them by narrating the parables, just before setting off, a bird inquired hoopoe about how long the journey will take. The hoopoe responded by elaborating on the seven stages they ought to cover to reach the Simurgh. The fourth stage, as narrated by the hoopoe, was the valley of detachment; he explained the stance by recounting a few parables, like the parable of the fly and honey. A fly yearned for honey; upon entering the garden, it saw a hive of honeybees. Her desire for honey became so much that she wanted to get honey at the expense of its freedom. She cried that she would give a coin(obol) to anyone who would let her enter the hive. Her condition was pitiful as she couldn’t think about anything beyond honey. Someone took pity on her condition and let her in the hive. As soon as she went into the hive, her legs entangled in honey. With the stuck legs, she tried her best to come out by fluttering her wings. But every single effort went in vain, and she sucked in honey more and more. In this pity, she mourned and mourned:

“This is tyranny; this is a poison. I am caught. I gave an obol to get in but would gladly give two to get out of it (Aṭṭār, Farīd -D, 2011).”

The allegoric characters were honey and bee, honey being the deceitful world and fly being the human desperate by desires. Once struck by these worldly desires, the person keeps on drowning in the swap. Setting the soul on the path of God needs to get detached from these material things. The hoopoe advised his folks that they must rouse themselves from apathy, and they ought to renounce the framework of the inner and outer attachments. These two steps are crucial for crossing the arduous valley of detachment. He further advised that if the folks will fail to renounce at this very step, then they will become more heedless and lost in the world and will fail to become self-sufficient.

Through this parable, Attar presented the idea that sometimes the results of our desires and goals don’t come out as we expected them to be. Sometimes we cannot approximate the level of damage our love for the world can bring to us. Thus we need to weigh our desires well. The world and its possession are deceitful, so the prime step in the ways of eternity is to make your hands empty from these worldly belongings.

Thus in the valley of detachment, the traveller is done with all the worldly affairs. This new disposition of the mind detaches him from the longings; at that stage, the aspirant becomes utterly needless. Now the soul only yearns for contentment and fullness. The craving for this solaced soul (Nafs-i Mutmainne) strips off the materialized yearnings and replaces them with moralized virtues. The soul which desires this placidity has its uninterrupted path toward God. Out of this, a destructive hurricane rises, and every single wave of the storm individually possesses the ability to annihilate kingdoms. At this stage, the aspirant has detached himself from the world up to the extent that the seven seas become mere a subtle water pool, the seven skies as a small curtain between him and the beloved.